Supported by ISS ESG

Environmental and governance issues have commanded the attention of sustainable investors in the past decade, and for good reason – integrating these principles into investment processes can lead to higher returns while promoting good corporate practices.

But it took the Covid-19 pandemic to bring into sharp focus issues of a social nature, including diversity, inclusion and equity at the workplace. It will take greater disclosure of employment data and more meaningful engagement with shareholders to better incorporate this aspect into sustainable investing.

The effort will pay off. Besides contributing to a more just society, a commitment to social principles translates into more profitable businesses. Research continues to show that companies with diverse leadership outperform those with homogeneous – usually white and male – composition at the top.

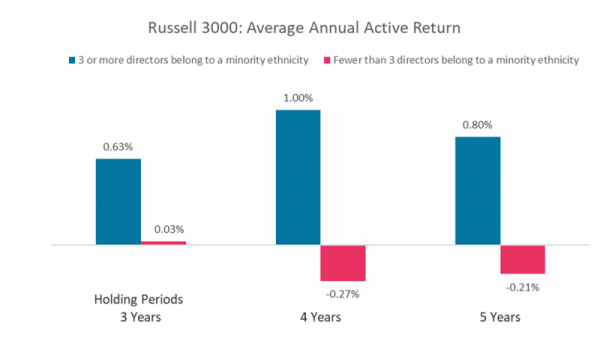

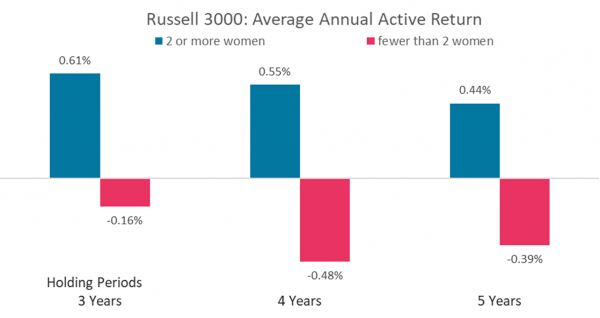

A recent study by ISS ESG, the responsible investment arm of Institutional Shareholder Services, found that companies with more diverse boards performed better than the average Russell 3000 over a period of three, four and five years. Separate studies analyzed the performance impact of including both women and ethnic minorities on corporate boards.

Source: ISS ESG Director & Executives Diversity Data as of Dec., 2020

Despite progress in getting more women and minorities on board of directors, investors say that diversity efforts need to target the broad workforce.

“You can’t just put some people on the board and think [the job] is done,” said Lydia Kuykendal, director of shareholder advocacy for Mercy Investment Services, the asset management program for the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and its ministries, at a recent D&I forum hosted by CleanTechIQ. “Diversity up and down the ticket is utterly important.”

That is because consumers, as a reflection of society, are diverse, so a company with managers and workers from different backgrounds, ethnicities and gender will better understand and serve them. In turn, diversity will lead to a more dynamic, efficient and profitable company.

Getting companies to act on issues of diversity and inclusion is no small feat, and the pandemic helped with raising awareness around the issues.

“Paid leave, health and safety, employee engagement…all of these have been concerning for sustainable investors for a long time, but rarely have they been the focus of attention,” said Heather Smith, lead sustainability research analyst at Impax Asset Management, an asset manager with $46 billion in assets under management, during the forum.

A significant increase in shareholder resolutions this year that sought greater workforce diversity reflects investors’ sharpening focus on the “S” of ESG principles.

According to ISS, 80 proposals concerning workplace diversity were submitted to Russell 3000 companies year-to-date through August, compared with 20 during the 2020 proxy season. ISS collects shareholder proposal data across a universe of 6,600 public companies in the U.S.

More than half of the proposals, or 44, asked for companies to make public a consolidated version of the Equal Employment Opportunity-1 report, filed annually by companies with more than 100 employees to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The report contains data on workers’ gender, race, ethnicity and job category, providing a snapshot of a company’s workforce profile.

The asset management arm of the New York City Comptroller’s office has been promoting this practice through shareholder engagement. It approached over 70 companies in the S&P500, based on their public statements around diversity, racial justice and gender equality, and requested they made their EEO-1 report public.

“Previous to last year, it was roughly 14 companies [that disclosed the report], now it’s up to 77 companies,” said Jimmy Yan, special counsel to the chief investment officer and Deputy Comptroller for asset management at the Office of the New York City Comptroller.

“We are really encouraged by the quick uptick in that practice,” Yan said during a panel at CleanTechIQ’s forum.

Shareholder proposals usually serve as a means to engage companies in dialogue – ISS data shows that of the 80 workforce diversity proposals submitted for the proxy ballot this year, most were withdrawn, which suggests companies’ agreement to provide the disclosure.

But even those that have so far been put to a vote – 11 proposals – garnered a median of 60% of votes in favor. In 2020, a total of 12 proposals that were put to a vote last year got a median 43% votes in favor.

One such proposal seeking information on gender and race pay practices was filed by Impax Asset Management at Oracle Corp. and got 46% of votes in favor, which is the kind of significant support that propels companies to take action.

“Pay parity isn’t an isolated factor, it’s not just about ensuring people in similar jobs get paid equally,” said Impax’s Smith, during the forum.

The firm hopes that greater transparency will help investors evaluate how promotions are handled, while attrition rates could reveal disparities in the treatment of employees, she said.

Another hurdle to achieving a clear picture on corporate diversity is the various legal barriers that prevent an employer from enquiring about the ethnicity and gender of employees, in particular in Europe. Besides, the definition of race is also complicated.

Some regulatory changes are supporting the quest for greater transparency, though. In the U.K., for instance, gender pay gap disclosure is required of companies with more than 250 employees. The information is available on a public website.

In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved last month a rule that requires companies traded on the Nasdaq Stock Market to publish a report yearly with information about the race, gender and LGBTQ+ status of its board of directors.

Under the SEC’s “comply or explain” rule, companies with at least five members on its board is required to have at least two self-identified diverse directors, with at least one woman and one from an under-represented minority or LGBTQ+.

The Nasdaq rule is “progress,” said Kuykendal of Mercy Investment Services. But it is problematic as it keeps in place a pattern in which “we force underrepresented groups and minorities to fight over scraps,” she said.