First in a series

A decade or so ago, few could have predicted that the marketplace for distributed generation — whether solar, wind, fuel cells, or something else — would be where it’s at today. Falling prices, new technologies, changes on the demand side — many factors came together to create the market of 2017.

Similarly, it’s impossible to say how distributed projects will change in coming years. One thing seems certain though: demand will stay strong, and money will continue to flow to such projects.

CleanTechIQ has been speaking to bankers, investors, project developers and other experts to learn exactly where that money is going to go this year, and what type of distributed projects will see the most demand. And while developments in distributed solutions are ongoing and rapidly evolving, it’s clear that distributed projects require further financing innovations to scale up investment.

Over the next few weeks we will be publishing detailed looks at these various project types, including brief profiles of some of the major players and projects. We start today with a broader look at distributed models for sustainability projects and how they are being financed.

There is, in fact, “tremendous interest” in financing distributed generation projects, according to Alfred Griffin, president of the New York Green Bank, the state-sponsored agency that works with the private sector to increase clean energy and energy efficiency investments and committed $250 million in 2016. An emerging set of financiers is interested in the deployment of cash-generating assets in fast-growing sustainability markets, and those financiers are finding an increasing number of credible platforms and project developers to invest in.

The majority of the deals that the New York Green Bank has been closing on recently have been residential solar, Griffin says. But the agency is also seeing growing deal activity in corporate and industrial (C&I) solar projects, community solar and energy efficiency retrofits.

There is also more project history and data available on the residential solar market, now that there has been a number of rated securitizations and refinancings of portfolios in both the public and private markets. This makes lenders more comfortable with making loans in this sector because they have a higher level of confidence that they can in fact refinance these projects in the future and lowers their risk, says Griffin.

Most of the distributed solar projects to date have been financed through power purchase agreements (PPAs), while most energy efficiency retrofits have been financed through energy services agreements (ESAs), says New York Green Bank’s Griffin.

And now, thanks to the sector’s maturity, we are seeing more solar deployment through traditional bank loan models that allow end-users to own their solar PV systems. They can then finance the bank debt with the cost savings the systems produce.

For example, the New York Green Bank, along with DZ Bank, the third-largest German bank, provided a $200 million warehouse line of credit to Mosaic last April to increase its ability to offer loans for residential rooftop systems via its online platform. Mosaic went on to close another $250 million credit facility with Deutsche Bank in November.

So who is installing these sustainable projects? The technologies are proving popular across a wide range of end-users, from residential homeowners to businesses and school systems. One of the biggest factors driving this adoption is the continued sharp fall in clean energy prices, which has made clean energy cost-competitive with fossil fuels. This pricing trend is widely expected to continue.

When it comes to energy efficiency projects, both residential and commercial, we are seeing increasing availability of Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing, allowing more installations of LED lighting and building control software systems, to take just two examples of popular building energy retrofits. PACE financing lets homeowners and business owners pay for clean energy and energy efficiency projects through incrementally increasing property tax bills over 10 to 20 years.

Finance the Portfolio – Lower the Risk

Among large banks interested in financing distributed asset projects in solar and energy efficiency, their primary interest these days is in “portfolio approaches,” in which many small projects are aggregated together in order to raise financing. This aggregation approach lowers the portfolio’s risk profile, spreads out transaction costs, and allows banks to deploy substantial capital into these projects to reach greater scale. “That is the most significant trend we’ve seen,” says Griffin. These markets, he says, are large and growing and show enormous potential for further growth.

These transactions often have a warehouse line of credit in place at first, which allows a project developer to aggregate a large portfolio of projects together with a bank. Then, for longer-term refinancing, the portfolio will graduate to the securitization market, or into a yieldco, a public company that bundles clean energy projects. There is a growing number of private placements of these securitized assets with institutional investors, and a growing appetite from insurance company investors in particular, according to Griffin.

Clean technology project developers are also actively raising project finance funds that enable them to offer no-money-down approaches to adopting these sustainable infrastructure technologies. This is helping to spur even greater adoption of distributed solar, energy efficiency and energy storage projects.

Overall, these distributed asset projects are increasingly meeting the financing criteria of traditional financiers, Griffin says, because they use established technologies, have a contract in place for the off-take of the project, and are managed by proven operating groups that can maintain the asset for the next 20 years. There is also greater standardization in the underwriting of these projects, which reduces transaction costs, he says.

There has also been a growth in the availability of insurance contracts that reduce the risk of clean technology projects for project financiers. This is expected to continue to grow, which will help spur even greater adoption of clean technology infrastructure projects.

Distributed asset projects tend to offer investors attractive attributes including yield and cash flows while generating returns that are uncorrelated to the broader financial markets. And because they are secured real assets, they tend to carry a lower risk/reward profile than traditional private equity deals.

Individual distributed asset finance deals are still relatively small, typically between $1 million and $50 million, according to Griffin. Because of that smaller size, they tend to fall below the radar of most major banks and infrastructure investors, opening up opportunities for alternative capital providers to fill the financing void.

This market is growing fast. The U.S. is expected to deploy 77.3 gigawatts of distributed renewables between 2016 and 2025, with the majority coming in solar installations, according to Navigant Research.

New Funds & Alternative Financiers

In addition to greater participation from banks, a growing number of private equity funds and alternative financiers are showing interest in providing “deployment capital” in the form of project equity and debt to help support these types of projects.

The capital for these funds is coming from high net worth investors, family offices and small institutional investors that are interested in both sustainability and in providing capital for critical infrastructure to make cities and businesses more resilient.

Financiers say they are interested in backing technologies such as rooftop solar, waste-to-value, water and wastewater, energy efficiency, agriculture and distributed energy storage for commercial customers.

Private equity fund managers tell us they prefer deals in the $5 million to $25 million range, as there is less competition from large infrastructure financiers. Projects in this range often use technologies that generate a higher rate of return because they are in the early phase of their development cycle as well. Such projects often boast equity returns in the mid-teens, investors say.

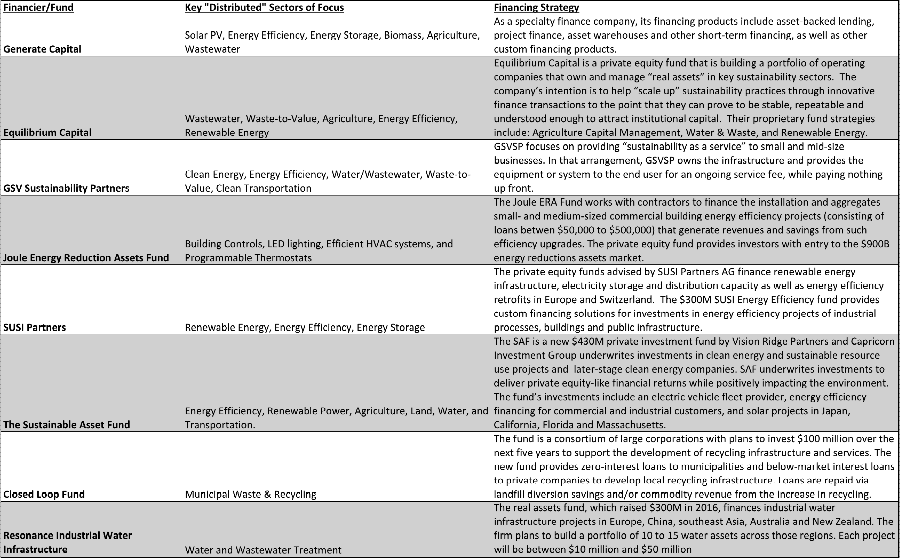

Notable Providers of Deployment Capital:

Financing of Sustainability Comes in Many Flavors

The financing of sustainable technologies deployments can take multiple forms depending on a wide range of factors including project type, the policy environment, and financing need. Clean tech deployment financing may come through as private equity, bank debt, project financing, corporate investment or government grants. Often, these projects attract a combination of these financing sources.

Silicon Valley Bank, a commercial bank that focuses on technology markets, offers capital in the $1 million to $50 million range to companies and projects in the areas of sustainability and resource efficiency. “We provide various forms of venture debt for earlier stage, venture-backed technology companies, term and working capital financing for growth companies, and a wide array of debt vehicles for larger companies,” says Matt Maloney, head of the bank’s Energy and Resource Innovation Practice. “We also provide project financing for renewable energy, in particular distributed energy assets.” The bank has a very optimistic outlook for the financing of both energy storage and energy efficiency, he adds.

Another established deployment financier, Hercules Capital, provides venture debt in the range of $10 million to $50 million to pre-revenue companies, which are typically at the series B or later funding stage and are looking to get a commercial plant up and running, according to Catherine Juhng, a vice president with the firm. Hercules will finance companies in all clean tech subsectors, she says, but lately has been focused on deals in the food and agriculture, distributed solar, and transportation sectors.

One of the key challenges in the development of sustainable financing products that allow institutional investors to invest in this space, according to Marshal Salant, Citibank’s global head of alternative energy finance, is matching capital providers with investment structures they will find most appealing. Referring to capital providers he develops these products for, “some like vanilla, some like strawberry,” Salant says. This has led Citi to develop MLPs, yieldcos, securitized products, project finance funds, Term Loan B financings and various other financing vehicles for distributed clean energy and energy efficiency projects.

Market Size

Due to their relatively small size, distributed projects are not always counted in many of the industry’s market size numbers or forecasts. And each project typically attracts a variety of capital sources, making financing data more difficult to track. Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), for example, only tracks small-scale asset financing of distributed rooftop solar in its “clean energy investment” figures, leaving out the financings of the several other growing distributed project sectors included in this article.

According to BNEF, small distributed rooftop solar capacity (projects of less than 1 megawatt) accounted for $40 billion worth of financing in 2016.

BNEF is predicting a huge increase in behind-the-meter distributed generation, to the point that such generation will account for some 10% of total electricity by 2040. This will happen as households add battery storage to small-scale solar PV systems.

If the definition of distributed projects is broadened, annual installed capacity across the global “distributed energy resources” market is expected to grow from 110 gigawatts in 2015 to 336 gigawatts in 2024, representing $1.9 trillion in cumulative investment over the next 10 years, according to Navigant Research. The technologies included in Navigant’s forecast include distributed solar PV, small and medium wind turbines, microturbines, stationary fuel cells, diesel and natural gas generators, distributed energy storage systems, microgrids, electric vehicle charging and demand response.

There has also been tremendous growth in the adoption of LED lights, which have grown from just 1% of the market in 2010 to more than 50% today. That growth will continue, with LEDs taking an almost 70% market share by 2020, driven by regulations and rapid technology improvements that drive down costs, according to Goldman Sachs (link to the pdf of their Low Carbon Economy report.)

We will explore examples of specific financing sources in upcoming articles. Among the specific sectors we will highlight are distributed solar, energy efficiency, battery storage, and waste and water.