As emerging economies such as China and India go from being among the largest emitters of carbon dioxide to some of the largest investors in renewable energy, those countries must also face the problems associated with having relatively little clean water.

Abby Joseph Cohen, an economist and senior investment strategist at Goldman Sachs Group, pointed out in a recent presentation that when discussions take place regarding a “new, cleaner future,” observers should factor in issues related to the scarcity of clean water in some countries. For instance, China and India, the two most populous nations on the planet, are significantly lacking in clean water. In certain provinces in China, said Cohen during her remarks at a Carbon Disclosure Project event in New York City, 80 percent of available water is too dirty for human or agricultural use, while 50 percent is too dirty even for industrial purposes.

“There is this connection between energy and water,” said Cohen. “And very often clean energy requires a great deal of water.”

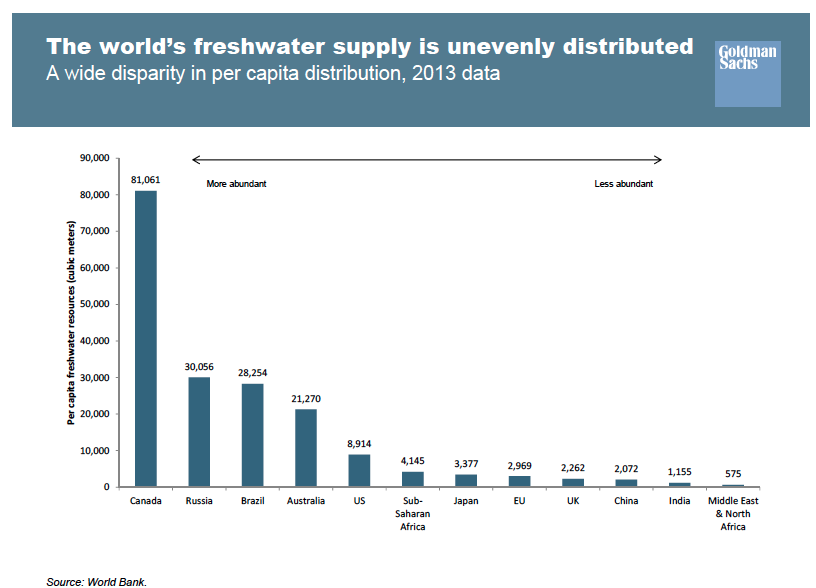

For example, Canada, Russia, Brazil and Australia are the most “well-endowed” with water resources when measured by the amount of fresh water resources per capita, according to World Bank data that Cohen cited. On the other hand, China, India and the Middle East and North Africa have far less abundant water resources. In addition, some of those regions are in the midst of political turmoil and war, Cohen added.

Yet while China faces a relative lack of clean water, the country is currently the world’s top investor in renewable energy, Cohen said. China is responsible for 23 percent of global investment in renewable energy capacity, while the United States is responsible for 16 percent.

“There were people who were skeptical about whether the Chinese were serious about reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” Cohen said. “The answer is: They really are very serious.”

Under the leadership of Chinese President Xi Jinping, the country has prioritized clean technology investments. In addition, in 2014 and again last year, China and the U.S. jointly announced measures to reduce carbon emissions. China agreed to lower its emissions after 2030 and also launched a carbon cap and trading system.

That’s crucial for China, whose reliance on coal and increasing traffic in its cities is environmentally unsustainable, according to a paper published last year by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, authored by Fergus Green and Nicholas Stern. Indeed, Cohen’s data on annual mean concentration of particulate matter show that Beijing is fourth in a list of cities around the world with the highest concentrations of particulate matter, behind Delhi, Dhaka and Mumbai.

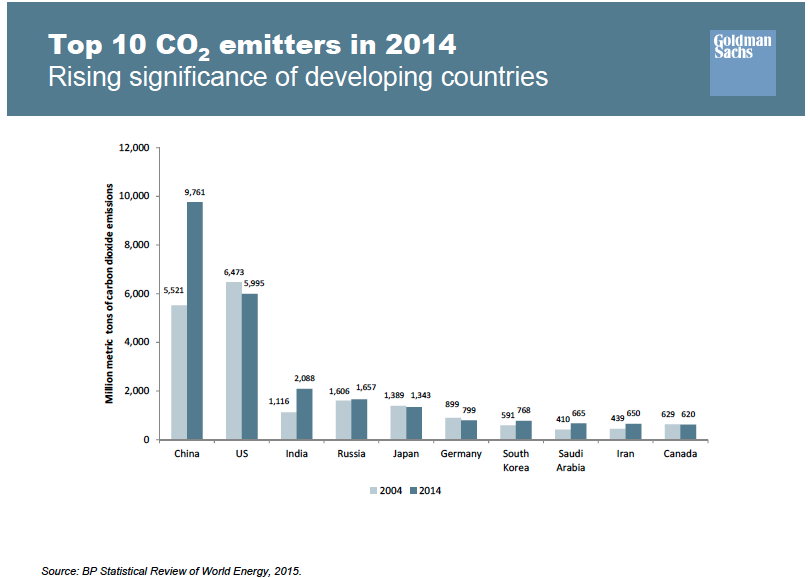

According to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy, China’s carbon dioxide emissions grew from 5.5 billion metric tons to 9.76 billion metric tons from 2004 to 2014. The U.S., which is now second to China, decreased from 6.47 billion to 5.99 billion over the same period. In addition, India’s emissions grew from 1.12 billion to 2.09 billion, while Russia’s emissions grew from 1.61 billion to 1.66 billion.

However, China is currently reforming its economic structure, finds the Grantham Research Institute paper, “China’s New Normal: Structural Change, Better Growth, and Peak Emissions.” Capital is shifting away from “heavy-industrial sectors (especially in low value-added products such as steel and cement) and toward service sectors and higher value-added manufacturing, as has been gradually occurring, will raise productivity as traditional industries decline,” the report states (download the report PDF.)

“Becoming a more innovative producer is particularly important to China’s aspirations to move up the global value chain,” the report reads. “China is beginning to play more of a leading role in various innovative sectors, including clean energy, drawing on its growing base of skills and research and development capabilities.”

The shift away from an industrial economy to a more service-oriented economy, plus investments in social services and healthcare, go hand in glove with China’s clean energy agenda.

Unfortunately, Cohen’s data show that the challenge in China is compounded by its lack of water resources. China is tenth in the world behind regions and countries such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the European Union, Japan and the United Kingdom in freshwater resources.

Water Technology Business Opportunities in China

Water and wastewater technologies are indeed big areas of focus for corporations in China, according to Matthew Nordan, founder of MNL Partners, a developer of clean tech infrastructure projects and joint ventures in China. Nordan, who recently spoke with CleanTechIQ about his firm’s projects, is a former partner at Venrock, the venture capital arm of the Rockefeller family, that was an early investor in companies such as Nest, Atieva, Boston Power, FINsix, and Phononic Devices.

Chinese corporations’ interest in water technologies is driven by the fact that the government is forcing industrial companies to clean up their operations with new regulations implemented last year, particularly around the discharge of wastewater. Many of China’s waterways are severely polluted, which has contributed to a major fall in its domestic agriculture production as well as becoming a source of public unrest.

Deep-pocketed Chinese corporations are looking for partnerships with Western clean technology firms to help them develop new water saving and re-use infrastructure projects, Nordan says. These Chinese corporations have a “tech problem,” he says, and need to develop joint ventures so they can import cleantech innovations from Western countries. MNL Partners helps structure these cross-border deals.

According to consulting firm McKinsey & Co., China has focused most of its innovation activity in consumer electronics and construction materials, rather than in science and engineering based innovations, such as cleantech and biotech. That means the business opportunity for U.S. clean technology developers to export their innovations to China is huge, as reported.

Membrane bioreactor (MBR) technology is expected to play a key role in China’s wastewater treatment, reuse and recycling industry, and is currently a $1 billion dollar market opportunity, according to consulting firm Frost & Sullivan.

Specific examples of water and wastewater projects in China include:

– Last June, Veolia announced it will build a biological treatment plant to treat wastewater from fertilizer producer LiuGuo Chemical, which will create additional fertilizer from the byproduct. Veolia also partnered with a major Chinese brewery implementing several cutting-edge water treatment processes.

– Norwegian firm Cambi expects to open the world’s second-largest thermal hydrolysis plant in Beijing next year, with a capacity of 134,000 tons per year. The process takes leftover sludge from the wastewater treatment process and converts it into methane, which is then burned to create electricity. Cambi now has contracts to build five such plans in China, which will treat approximately 1,200 metric tons of dry solids per day in Beijing, according to a release.

– Late last year, BioGill, an Australian developer of bioreactors and biofilters that use microorganisms to ‘eat’ waste out of the water, shipped 10 units to China that will be used in aquaculture projects.

– Dutch firm Nijhuis Industries, which combines organic waste with wastewater treatment technologies, developed a water treatment plant for China’s largest oil and gas producer.

Goldman Focused on Global Climate, Water Problems

In November, Goldman Sachs expanded its global clean energy target to $150 billion in financings and investments by 2025 to “facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy.”

“We are providing financing that allows other companies to do good work in this area,” Cohen said in her speech. The company is providing funding for huge infrastructure needs, such as water and wastewater, not just in developed nations but increasingly in emerging markets, she added.

The “clever financial innovations” being developed include wet related catastrophe bonds, new climate related indexes and asset management products, Cohen said.

Another “clever” financing led by Goldman was the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority’s $350 million, 100-year green bond offering in 2014. The money was to fund “new infrastructure to address combined sewer overflow issues, helping to improve water quality, reduce flood, and restore the District of Columbia’s waterways,” Goldman says.

No previous green bond has carried a 100-year maturity, according to data provider Dealogic; that long timeframe “matched the life of the asset and spread financing costs across generations that will benefit from the project,” Goldman says. It was also DC Water’s first-ever green bond issue as well as the first “certified” green bond in the U.S. debt capital markets with an independent second party sustainability opinion, DC Water said at the time.

Investors More Aware of Climate Investing

More institutional investors, such as pension funds and endowments, are paying attention to these issues, according to Cohen.

“As we have seen the mainstreaming of climate-aware investing, and more money is paying attention to these issues, the performance has improved,” she said. She explained that the improved performance of environmentally friendly companies is driven by the fact that institutional investors are increasingly considering “green performance” of companies in their analysis.

Goldman’s own research supports this fact, Cohen said. “Typically companies that score best on ESG indexes have the best performance as companies, the best internal returns, the best returns on equity, the best employee retention, the best reactions from their communities, and the securities that they issued also perform well.” Furthermore, she said, the cost of capital for those companies is lowered because their price to earnings ratio is higher and the rates they must offer when issuing new bonds are lower.

Cohen said she now strongly encourages the firm’s equity research analysts — who disseminate their research to the institutional investor community — to take these environmental factors into consideration when they analyze companies around the world.

“We believe that paying attention to the environment is not just the right thing to do, but we also think it’s very good business,” she said. “Something that makes shareholders feel good, employees feel good. Doing the right thing and being rewarded in capital markets is appropriate. We can dedicate resources to these efforts.”