The next phase of cleantech investment is upon us but it is necessary for investors and startups to reassess profit expectations in order to maximize the potential of their investments and technologies, delegates at Clean Tech Future II in San Francisco were told last week.

The first stage of investment in cleantech products failed to reward investors with revenues and profits they had set their sights on, a number of speakers said.

“Cleantech failed to capture the imagination of the industry, and the average return of 0.5% is not what capital providers signed up for,” said Rob Day, partner at Black Coral Capital, a venture capital firm.

However, Day believes all forms of investors are coming back to the market after the last failed wave of funding but they will require a change in mindset to be successful, shunning wishful thinking for a more pragmatic approach.

This change is especially problematic for venture capital and private equity firms, speakers said, and will improve the position of investors willing to commit for longer periods of time, along with helping startups realize their maximum potential.

“Companies must be tested far more rigourously to ward against failures, while not all startups need to seek capital immediately, capital should only be raised when absolutely necessary,” Day said.

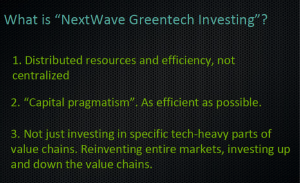

Day, and others, believe strongly that the new wave of investment will flow into distributed and shared resources that increase efficiency, with goods ownership taking a backseat to collaborative efforts. The Clean Energy Collective, a community-owned solar generation program is an example that Day drew upon, with Black Coral Capital having already invested.

Scott Jacobs, managing director and co-founder of investment firm EFW Partners, concurred with Day’s view, calling for investors to have more realistic expectations of the industry.

“Rather than expecting 10x in 3 years, maybe 3x in 10 years should be the aim.”

Investors also need to broaden their horizons, Jacobs said. “A successful investor will thematically invest capital across asset classes.”

EFW has invested heavily in Sungevity, a company leasing rooftop solar panels to homeowners so they do not have to make a capital investment, along with SNTech, a firm aiming to reduce electricity usage from motors used for heating and cooling.

Investors must be more innovative with their investment techniques, Jacobs said, suggesting cooperation between corporates, governments and private equity firms in order to utilize a multitude of skillsets to enhance returns.

All forms of financiers must “look up and down the value chain rather than pigeonholing themselves into one sector,” Jacobs said.

However, the burden is not only falling on investors to change their ways. As the industry has failed to offer financiers the growth originally expected, “companies need to deliver better returns in order to incentivize the return of capital”, Jacobs believes.

Examples of this included the renewable power development and energy optimization sectors, while both provided strong returns between 2000-2011.

Corporate roles

Vincent Schachter, vice-president of R&D at Total New Energies, a renewable energy project developer, said that major corporations could play a more important role in funding startups going forward.

“Corporations are already overtaking venture capital firms as the main source of funding,” Schachter said. The ability of major companies to endure the long and capital-intensive development of products and power to deploy at scale has improved their position in being chosen as a source of funding, while also affording startups the ability to take a long-term view, rather than being pressed for quick returns.

Schachter said the venture capital view of quick returns could harm startups’ long-term potential, whereas major corporations can offer the ability for startups to engage in a long-term approach.

He warned that neither startups nor corporations can do it alone and that their “cooperation could be catalyzed and stabilized by third parties such as angel investors or venture capital firms”.

Total New Energies joined EFW in the solar sector, taking a majority stake in SunPower, along with investments in a number of research and development programs across the world.

Vicky Sharpe, president of Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC), a non-profit government funded foundation, agreed with Schachter’s view, saying that patient capital can breed stronger companies.

“It is a difficult, patient game,” Sharpe said. “It requires a different mindset. It’s not easy to put quality before timing.”

Sharpe added that the future of investing could be helped by government-aided companies such as SDTC, sovereign-wealth funds like the Singapore’s GIC and also pension funds, where growth expectations can give startups more time to achieve their maximum potential, without sacrificing quality.

The value of patient capital has been demonstrated by SDTC’s investments, with a 4-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 80% being realized in EcoSynthetix, a company using biobased materials to replace petroleum-based products. A 4-year CAGR of 34% was also reached following an investment in Westport, a natural gas vehicle engine maker.

SDTC has invested heavily in energy exploration and production, helping hydrocarbon explorers minimize their carbon emissions, especially in Canada’s tar sands, where technological advancements in carbon storage could make oil extraction carbon neutral.

Qatar Investment Authority, the sovereign wealth fund of the Arab emirate, has invested heavily in cleantech, supporting the Californian-produced Karma hybrid vehicle. Similar cases have been seen with Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), the world’s largest sovereign fund, which is aiming to provide $10 billion a year into clean energy investment.