Energy storage companies are at an exciting—and dangerous—tipping point, says Alan Gotcher, CEO of Xtreme Power. On one hand, money from the federal stimulus, which fed so much growth in the industry, is drying up.

“We’re coming off the stimulus,” says Gotcher who estimates that at his company, “two-thirds of our projects were from stimulus grants of some sort.”

Meanwhile, most energy storage companies predict that technology improvements and growths in scale will allow them to lower prices by three to five percent every year in coming years, which is beginning to rewrite the old rule that energy storage projects are too expensive to pay for themselves.

In some markets, projects “are beginning to pencil out where there is a real project return” on investment, Gotcher said during the recent Agrion Energy & Sustainability Conference in New York.

Xtreme’s renewable integration on a 1.2MW solar farm in Lana’i, Hawaii.

Xtreme Power has installed 77 megawatts of storage capacity across 13 sites since its founding in 2004, Gotcher said. Those have included a storage system installed six years ago at the South Pole, plus its latest project, which involved 36 megawatts of storage at a Texas wind farm for Duke Energy. The current cost of installation, provided the developer does not have to improve surrounding infrastructure such as roads, is between $1,500 and $1,700 per kilowatt hour, said Gotcher.

Now, as stimulus money ends and project financing becomes more uncertain, “I think the energy storage businesses right now are facing that chasm,” said Gotcher.

Investors may have noticed a chasm of a different sort. Energy storage companies raised $472 million for 43 projects during the first two quarters of 2011, according to Convergent E&P. During the same period of 2012, only 13 projects were funded, for a total of just $83 million, an 84-percent decline. Indeed, the energy storage industry appeared to flounder even more than other cleantech industries, which together saw investment totals dip 33 percent in 2012 to $6.46 billion, according to Cleantech Group.

This retrenchment by investors is seen as particularly vexing when it comes to energy storage, which is seen as the key that could unlock billions of dollars of investment in industries such as solar and wind by moderating the variable and unpredictable nature of electricity from renewable sources.

To underscore just how important such advancements may be, DBL Investors participated in an $11-million funding round for Primus Power, developer of grid-scale energy storage technology. Primus had high demand for its products from government entities such as the Department of Defense and the Bonneville Power Administration, even before they had finished development.

“(T)hose contracts were signed even though the system isn’t ready yet because they’re that desperate to integrate storage,” Nancy Pfund, a managing partner at green-tech heavyweight DBL Investors, said at a recent panel discussion.

This pressure to deliver on the long-anticipated returns of energy storage is leading to a combination of opportunity and peril for the industry, the panelists agreed. In the positive column, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s ruling in June of last year to shorten service schedules from one hour to 15 minutes, thereby allowing for the natural variability of renewable energy sources, is “a terrific ruling for fast-acting assets, of which chemical storage is one,” Gotcher said.

But months later, the agency has yet to complete its final rulemaking, including how to calculate topline revenue, which remains a major stumbling block.

“Until that’s done, I don’t think any utility who is looking at the situation in a balanced way is going to make multi-million-dollar decisions to put hundreds of megawatts into virgin markets,” Gotcher said.

Once the rule is finally in place, energy storage companies will be able to expand in several areas, including offering ancillary services, said Bahman Daryanian, who researches the smart power industry for GE Energy Consulting.

The ability to smooth out peaks and valleys in power delivery, perform time arbitrage to sell electricity during periods of high prices, monitor performance metrics of the system, and delay potentially expensive replacement of transmission lines may provide as much value to utilities and electricity co-ops in coming years as the ability to store energy itself.

“I think you’re going to see lot more demand for energy storage ancillary services on the wholesale market side,” Daryanian said.

David Roberts, CEO of EnerDel, a lithium ion battery manufacturer, agreed. His company has developed 3 megawatts of utility-based storage in 2012. It plans to build an additional 8 megawatts this quarter, and a total of 20 through all of 2013, he said.

Lightning Motorcycles will use Ener1’s batteries in its wicked-fast Lightning Superbike.

Some of that success so far has come from increasing sales of ancillary services, including backup power to customers in developing countries, “which have very unstable grid conditions or unreliable equipment,” Roberts said.

As the capacity of storage installations grows, companies are able to increase efficiency by offering a wider array of services and storage options. While perhaps best known for its lithium ion technology, Xtreme Power has four other kinds of battery technologies to handle different project conditions, such as whether the storage system must regulate subtle variations of electricity delivery over many days, or instead manage large fluctuations between energy use and energy storage over just a few hours.

“We can provide any of those options at megawatt scale, singularly or in any combination,” Gotcher said. “So there’s a lot of flexibility in chemical storage to tailor a unique solution” and bring prices down.

Even as they reduce prices and bring new services to market, electricity storage companies face uncertainty on many fronts, the panelists agreed. One difficulty is the inherent mismatch on investors’ return on investment, Roberts said. Battery manufacturing requires advanced, high-output and expensive manufacturing equipment. For the best returns, companies and investors want those machines “to run full-out, 24-7,” he said.

Unfortunately, they can’t always do that.

“These projects are peaky, so they tend to need a lot of megawatts for a short amount of time, and they tend to go away,” said Roberts. “So it puts a lot of stress on the battery companies in our business model and trying to sustain manufacturing capacity.”

Another area of uncertainty is the U.S. military, already one of the largest funders of electricity storage research, Stephen Marlin, manager of advanced technology at General Motors, said at a recent Columbia University Energy Symposium. Finding ways to conserve energy would save the military money, and possibly reduce casualties, since troops would not need to escort as many deliveries of fossil fuels to forward positions.

Investment by such a large player would also drastically boost capacity and lower prices.

“As opposed to just paying the energy bill, which for the D.O.D. is tremendous, its more about energy as a strategic asset,” Roberts said.

There are problems, however. Xtreme Power has a contract to develop a storage system for a secret military project, Gotcher said during the panel. Gotcher is loathe to pursue more work with the military, though, because the Department of Defense maintains the right to cancel any project at anytime.

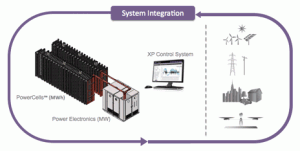

Xtreme’s Dynamic Power Resource is a fully-integrated energy storage and digital power management solution.

“When the defense department can back out of any contract at their sole discretion,” said Gotcher, “that’s a hard business move.”

In addition, even though there has been talk of building micro grids and storage capacity at the military’s large permanent bases, including in the U.S., “I’m a bit skeptical,” Gotcher said.

Given the low cost and high stability of the current American electrical grid, and the likely drop-off in military spending in coming years, “when you try to island a military base, costs are going to go up. So there’s going to be a tradeoff between what is security worth and what is it going to cost to implement.”