Most cleantech investors have certain factors they consider before placing bets, including profit potential, new technologies and tax credits. But what if you’re a fund manager invested in blue chip companies such as Facebook, Apple, Hewlett Packard or Dell, partially for what you believe are those companies’ strong environmental track records, only to find Greenpeace activists scoring world headlines flying a blimp over Mark Zuckerberg’s office or painting a giant protest sign on HP’s roof?

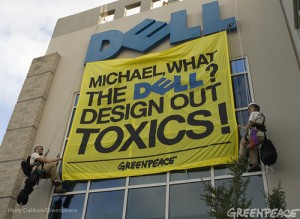

Another example: When Dell computers reneged on a promise to remove toxins from its products by 2009, Greenpeace activists hung a massive banner from the company’s headquarters in Texas that read “Michael, What the Dell? Design Out Toxics!”

When Michael Dell met with Greenpeace Executive Director Radford, “he said next time, please come to my office through the door,” Radford says. Greenpeace pulled a similar stunt with Hewlett Packard, only to give the company kudos two years later for leading the industry as the cleanest electronics manufacturer.

Instead of protesting from rooftops, these days Greenpeace is walking through a lot more office doors of CEO’s. That change in strategy is driven by the realization that private companies, not governments, now have more political power to drive environmental change, or to block it, Radford says.

Rather than fighting first for new laws, which industry can effectively block, Greenpeace pressures a few large companies in an industry to change their practices. This increases those companies’ costs, which turns the companies themselves into activists for industry-wide environmental change.

“Direct action is the just the tip of the iceberg,” Radford says. “For these early companies that move, it’s in their financial self-interest to get every other competitor doing the right thing.”

Take the example of Duke Energy, one of America’s largest energy companies. Greenpeace has tried pressuring Duke directly to add more renewables to its production mix, only to get rebuffed.

So now the environmental group is targeting one of Duke’s few growth opportunities: Power for electricity-hungry data centers. That campaign has included:

– Facebook. The granddaddy of all social networks is an organizing boon for Greenpeace, which uses the site to gain signatures on petitions and plan protests. Greenpeace also created a campaign called “Unfriend Coal,” a Facebook page that successfully pressured Facebook away from building another coal-powered data center into building a hydropowered center in Sweden.

– Apple. The company has promised to use renewables to power its data center in Maiden, North Carolina, but Greenpeace is pushing the computer giant to do more, forcing Apple to do something it normally avoids: Play defense.

– Amazon and Microsoft. Last June, activists hung a banner from Amazon’s new headquarters in Seattle (and directly facing Microsoft’s offices), asking both companies “how clean is your cloud?” Not very, apparently. In a report published in April 2012, Greenpeace gave both companies a sub-14% score on its clean energy index (out of 100), and assigned both a failing grade on energy transparency. The protest may have produced immediate results: The very same week, Microsoft announced it would build a power plant for one of its new data centers powered by sustainable fuel.

“If Duke has so much power over government decisions, who can we influence?” Radford says. “You have to go after their clients in the industry.”

This new focus on partnering with companies to effect industry-wide change could change the landscape for investors. Greenpeace targeting a company like Microsoft could force the software giant to spend more money than its competitors on green solutions, possibly reducing short-term profits. But it also could create investor opportunities if it means more efficient operations for Microsoft in the long term, or by boosting demand for products and energy from cleantech companies.

“What we do is not anti-business,” Radford says. “Doing the right thing for the environment is also doing the right thing for your company and for your investors.”

Not that Greenpeace has given up targeting companies it labels as the worst offenders. In a report published this week, the organization called attention to the 14 biggest coal, oil and natural gas extraction projects currently in planning phases around the world, including Peabody Coal’s plans to build five coal export terminals along the West Coast (which together would emit as much CO2 as all of Mexico, the group claims), and Shell’s controversial Keystone XL pipeline connecting the Canadian tar sands to refineries along the Gulf Coast.

If these projects move forward, the world will pass the “point of no return,” according to the report, after which it will be impossible to slow or reverse global climate change. Greenpeace activists have targeted another project mentioned in the report, plans by ExxonMobil and Shell to drill for oil in the Arctic, by trying to block the companies’ ships at sea. This resulted in a novel defense by Shell, which unsuccessfully sued Greenpeace in Amsterdam to bar activists from blocking its ships in the Arctic.

Greenpeace may also create opportunity for cleantech investors by pushing for more stringent emissions laws at the federal and state levels. The group welcomed the EPA’s new rules limiting carbon emissions from new power plants, but criticized the agency for including loopholes that would allow power producers to continue polluting at current levels for up to a decade. Greenpeace also is pushing various states to implement new renewable energy standards, and lobbying to protect existing state regimes including in North Carolina, which is being targeted by the American Legislative Exchange Council, an industry-supported lobbying group.

This hybrid strategy, trying to change corporate behavior from the inside while still pushing legislative change from the outside, is the key to Greenpeace’s new direction, Radford says.

“We’re working to find companies that are willing to lead and work them to push rules that bring the laggards up,” says Radford. “And meanwhile we’ll continue to work to pressure Congress, state legislatures or the ballot.”